Bonus material - Animation

Updated to Gio 0.8.0 as of April 4th 2025

Goals

The intent of this section is to discuss a slightly more advanced topic related to animation, namely how and when we invalidate a frame, what that actually means, and how to code well with it.

Outline

The outline of this bonus chapter is as follows:

- First we discuss what it means to invalidate a frame

- Then we look at two different method calls to do so

- Finally we discuss an alternative pattern to generate and control animation

1. What is Invalidate?

Gio only updates what you see when a FrameEvent is generated. This can be for example when a key is pressed, mouse is clicked, widget receives or loses focus. That makes perfect sense, with refresh rates of up to 120 frames per second for modern devices, chances are that what should be displayed quite often is identical to the last frame.

Quite often. But not always.

One exception to this rule is animation. When animating, you want it to run as smooth as possible. To achieve this, we need to ask Gio to redraw continuously. And without triggering events we need to explicitly tell Gio to do so. That is done by calling invalidate.

2. Two ways to invalidate

There are two alternatives, let’s look at both:

- op.InvalidateCmd{}.Add(ops) is the most efficient, and can be used to request an immediate or future redraw

At time.Time. - window.Invalidate is less efficient, and intended for externally triggered events. But it’s also the right option if you want to invalidate outside the layout code. One example of that is in Chapter 7 - Animation where we had a separate tick-generator.

Example 1 - op.InvalidateCmd{}

Remember how the progress bar is one of the rigids we lay out:

// PREVIOUS CODE

// The progressbar

layout.Rigid(

func(gtx C) D {

bar := material.ProgressBar(th, progress)

return bar.Layout(gtx)

},

),

We now expand that with its own personal timing logic:

// NEW CODE

// The progressbar

layout.Rigid(

func(gtx C) D {

bar := material.ProgressBar(th, progress)

if boiling && progress < 1 {

inv := op.InvalidateCmd{At: gtx.Now.Add(time.Second / 25)}

gtx.Execute(inv)

}

return bar.Layout(gtx)

},

),

In other words, if we’re still boiling, Execute( ) and InvalidateCmd 1/25th of a second into the future.

There’s also an example on this in the architecture document

Example 2 - w.Invalidate()

If however you prefer to set the framerate using a central ticking progressIncrementer, there’s an example of w.Invalidate() from Chapter 7 - Animation, and one in kitchen from the front page of gioui.org. To repeat the former:

func main() {

// Setup a separate channel to provide ticks to increment progress

progressIncrementer = make(chan float32)

go func() {

for {

time.Sleep(time.Second / 25)

progressIncrementer <- 0.004

}

}()

// ... the rest of main

}

func draw(w *app.Window) error {

// ...

// listen for events in the incrementor channel

go func() {

for range progressIncrementer {

if boiling && progress < 1 {

progress += 1.0 / 25.0 / boilDuration

if progress >= 1 {

progress = 1

}

// Force a redraw by invalidating the frame

// w.Invalidate() // This is replaced by op.InvalidateCmd for the progressbar on line 211

}

}

}()

3. - Replacing w.Invalidate() with op.InvalidateCmd{} - what’s the effect

So what’s actually the effect of using InvalidateCmd{At time.Time} instead of the central ticker?

Take a look in the code for the animation. You’ll find the new op.InvalidateCmd{} on line 211, and the old w.Invalidate() on line 84. Try changing running either one or the other to see which one performs best.

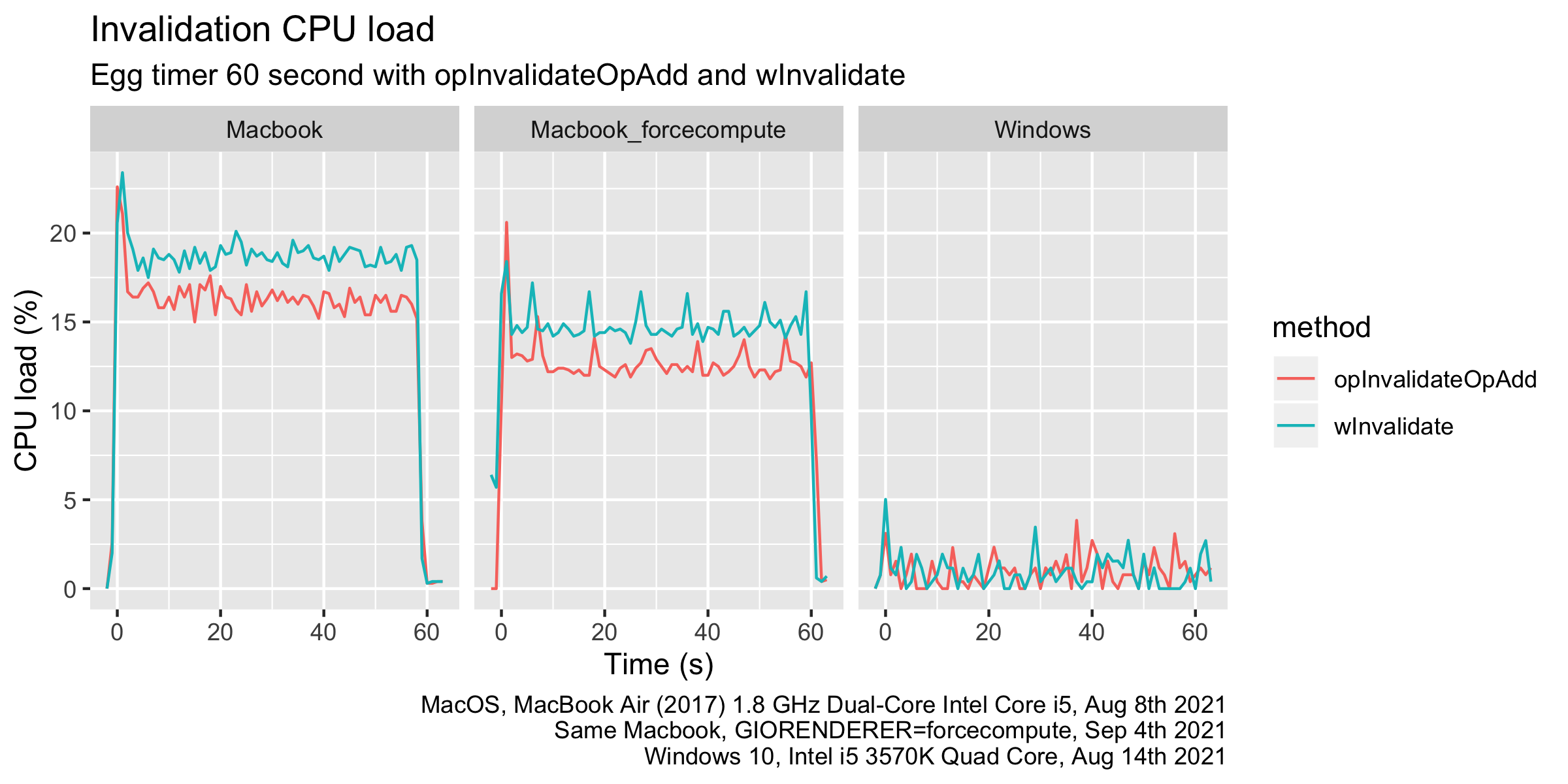

To try it out I ran three 60 second boils, one with each Invalidate method, both on my Macbook and my Windows desktop. On the Mac one was run with the old renderer, and one with the new using GIORENDERER=forcecompute go run main.go.

Without forcecompute the 2017 Macbook Air ran op.InvalidateCmd{} at about 16-17% CPU, while w.Invalidate() consumes around 18-19%. Those levels drop to ca 12% and 15% with the compute renderer. The level is fairly high, but the difference is not that large. Still it’s worth knowing the effect of each invalidate technique. On my Windows machine the load is much smaller with no meaningful difference between the two techniques.

A general pattern

My friend Chris Waldon came through with this pattern:

In my Gio applications, I have found a pattern that I think works well for encapsulating animation logic. It allows you to hide the management of the invalidation behind an API, and to compute the progress as a function of time. It eliminates the ticker goroutine altogether, though I almost worry that it makes the app less cool.

Sound’s intriguing, right? You can find the raw code in his repo. The code is from July 2021, and not updated to the latest version of Gio but let’s examine it a bit here none the less.

An animation struct

First replace the state variables boiling and boilDuration with a struct that knows when we started, and how long it should take:

// animation tracks the progress of a linear animation across multiple frames.

type animation struct {

start time.Time

duration time.Duration

}

var anim animation

This allows us to create methods to animate next frame and eventually end the animation. This is where op.InvalidateOp{}.Add() is called.

Also, note how it uses gtx.Now instead of time.Now, most importantly ensuring the animation is synchronized, but also avoids some overhead from time.Now.

// animate starts an animation at the current frame which will last for the provided duration.

func (a *animation) animate(gtx layout.Context, duration time.Duration) {

a.start = gtx.Now

a.duration = duration

op.InvalidateOp{}.Add(gtx.Ops)

}

// stop ends the animation immediately.

func (a *animation) stop() {

a.duration = time.Duration(0)

}

Finally a method to report on progress:

- Are we still animating?

- And if so, how much is done?

// progress returns whether the animation is currently running and (if so) how far through the animation it is.

func (a animation) progress(gtx layout.Context) (animating bool, progress float32) {

if gtx.Now.After(a.start.Add(a.duration)) {

return false, 0

}

op.InvalidateOp{}.Add(gtx.Ops)

return true, float32(gtx.Now.Sub(a.start)) / float32(a.duration)

}

Start simplifying

With that in place we can simplify the startButton.Clicked() code to:

case system.FrameEvent:

gtx := layout.NewContext(&ops, e)

boiling, progress := anim.progress(gtx)

if startButton.Clicked() {

// Start (or stop) the boil

if boiling {

anim.stop()

} else {

// Read from the input box

inputString := boilDurationInput.Text()

inputString = strings.TrimSpace(inputString)

inputFloat, _ := strconv.ParseFloat(inputString, 32)

anim.animate(gtx, time.Duration(inputFloat)*time.Second)

}

}

Tidy up the loose end

At the, since we removed the boilDuration variable, we instead use anim.duration.Seconds():

// Count down the text when boiling

if boiling && progress < 1 {

boilRemain := (1 - progress) * float32(anim.duration.Seconds())

What about our ticker-channel?

All code related to the progressIncrementer channel, both variables, reading and writing to the chan, is removed.

We’re not going into more detail about the pattern here, but know it exists and has some pretty neat functionality that takes care of state and status for your animation.

Comments

Summing it all up, I hope this has shed some more light on the in’s and out’s of animation in Gio. As so often, it depends what’s the best solution. Showcasing a demo to impress? Go for smoothness. Minimizing work? Go for animation in steps. High end vs low end user hardware? Splurge or conserve as you see fit.

Just be conscious about the trade-offs and know some of the techniques that can assist.